Before looking into the question: Does FSC guarantee sustainability? What is FSC?

FSC®, or the Forest Stewardship Council, is a voluntary forestry certification program designed to provide consumers with confidence that the wood or wood-based products they buy originate from sustainably managed forests.

However, FSC® does not guarantee sustainability in itself; instead, it offers a framework for sustainable forestry practices. This program establishes guidelines for logging companies to follow. In exchange for adhering to these FSC® guidelines, logging companies can certify their timber with the FSC® stamp and potentially command a premium price for their products. It’s important to note that FSC® does not directly inspect logging companies for compliance. Instead, independent third-party auditors are responsible for verifying that companies adhere to FSC® standards.

One key aspect of FSC® standards is the maintenance of a complete chain of custody. This means that a consumer can trace the timber’s origin, the forest it came from, and its ownership throughout the entire journey from origin to end destination. This transparency is a fundamental principle of the FSC® certification program, ensuring accountability and promoting sustainable forestry practices.

Defining Sustainability

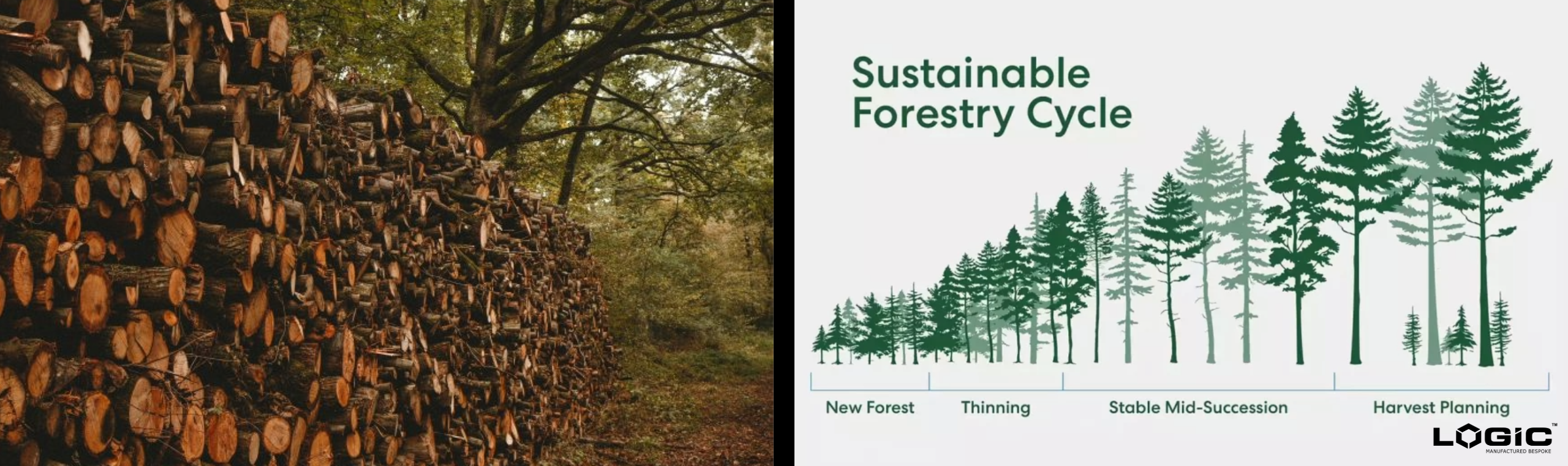

Sustainability, at its core, aims to meet our current needs while safeguarding the well-being of future generations. Yet, its precise definition can be elusive. In recent times, it has become an umbrella term for anything that leans towards being environmentally friendly.

Does FSC guarantee sustainability in Logging?

In the context of logging, sustainability entails striking a delicate balance between the demand for timber and the forest’s capacity to regenerate without harm. While this equilibrium seems attainable in theory, the reality often leans towards deforestation even in seemingly sustainably managed forests. A telling example comes from Kalimantan, an Indonesian part of Borneo, where independent activists discovered a paradox. Despite areas certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC®) exhibiting lower deforestation rates compared to non-certified regions, these certified areas displayed more ‘holes’ in the forest canopy. These gaps emerge when individual trees are logged, disrupting the ecosystem below by allowing unfiltered sunlight to reach the forest floor.

FSC Sustainability Evidence

While conclusive meta-data regarding the guarantee of sustainability through FSC® certification is limited, smaller studies point to positive environmental impacts in forestry management:

Miterva et al., 2015: In a case study focusing on Kalimantan, this research revealed that between 2000 and 2008, FSC® certification reduced overall deforestation rates by 5 percentage points.

Medjibe et al., 2013: This study compared FSC®-certified forests with conventionally logged forests in Gabon, Africa. It found that in FSC® areas, logging led to a 7.1% decline in above-ground biomass (AGB), while conventionally logged areas experienced a steeper 13.4% AGB decline.

Challenges in FSC’s Sustainability Assurance

One significant concern with the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC®) is the reliability of its auditing system. Competition among auditing bodies vying for contracts with logging companies has sometimes compromised inspection quality, especially in less economically developed countries where corruption is prevalent.

An investigation by Earthsight exposed unethical practices in Ukrainian timber labelled with the FSC® stamp, even making its way into Ikea’s supply chain. Widespread malpractice and corruption in state-owned Ukrainian logging companies were found, undermining the FSC’s oversight.

Another issue is the high cost of FSC® certification, limiting its reach to mainly northern European and American forests. Smaller logging operations in tropical hardwood-rich regions, like the Congo Basin, often can’t afford FSC® certification, hampering their competitiveness against larger, often foreign-owned companies.

The endorsement of FSC® by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) is a vital indicator. Recently, several NGOs, including Greenpeace, disassociated from FSC®. While the WWF has continued its support since 1993, a withdrawal would signify a significant turning point for the organization.

We recommend using or specifying FSC® because there are not many other viable options. In this article, we have not mentioned other forest protection schemes like the Program for Endorsement of Forest Certification, but their rules and results are even weaker than FSC®. For a more details comparison between FSC® and similar schemes please read our blog here.

In theory, FSC® rules should result in sustainable forestry and certain cases it does, see the examples above in this article. However, we feel these small wins are largely outweighed by the inherent flaws in the FSC® system.

Another issue to bear in mind is the carbon impact of transporting the timber. From a sustainability standpoint, using a UK grown timber, such as Oak or Douglas-Fir, is much more beneficial than using a Tropical hardwood grown in West Africa, such as Iroko or Opepe, because the timber only has the travel 100 miles or so rather than 6000 miles.

https://news.mongabay.com/2017/09/does-forest-certification-really-work/